In years gone by, I’ve tended to treat the unseen poetry component of the GCSE English Literature...

School Leadership and Inherent Knowledge

In A Theory of Expert Leadership, Amanda Goodall argues that leaders with ‘inherent knowledge of the core business activity’ are more likely to perform effectively than ‘professional managers’ or ‘generalists’. Inherent knowledge, as Goodall defines it, is both explicit (i.e. codified, transferable) and tacit (i.e. intuitive, experiential), and is acquired through a combination of education and practice. To emphasise the importance of it, she puts forward a number of testable hypotheses. For example:

- Organisations led by leaders who have inherent knowledge are more likely to yield greater innovation

- A leader who has inherent knowledge will demand higher quality from core workers

- Expert leaders will be viewed as more credible by core workers, which will extend their influence

- Expert leaders may be less likely to impose a culture of constant change management

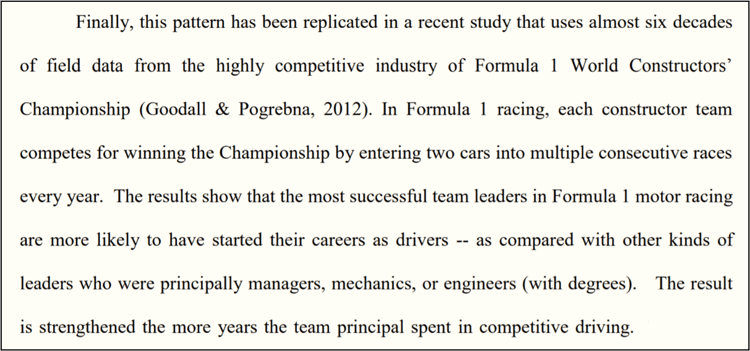

Goodall cites a number of supporting studies. For example, there’s one about basketball: former All-Star players seem to make better coaches. There’s one about hospitals: there’s a correlation between the presence of physician-CEOs and overall hospital quality. And, finally, there’s one about F1: former drivers seem to be more successful at leading teams than those without experience of driving competitively.

There are plenty of connections to be made with our own ‘core business’ of education. Most obviously, that inherent knowledge is vital for the successful running of a school. Leadership teams that lack, say, a deep understanding of the curriculum in its various forms or the characteristics of effective teaching and learning are unlikely to make informed, constructive decisions.

One of the ways in which this deep understanding can be fostered is through professional development: reading widely, attending conferences, engaging in debate, conducting research, participating in training, and so on. And another is through gaining plenty of experience in the classroom. Both are equally important, but it’s the latter – in my opinion – that is sometimes undervalued or too easily dismissed.

Doing your time, so to speak, and staying in-post long enough to enjoy successes and learn from failures is vital to forming an acute understanding of the complexities involved in educating students. I’ve made so many mistakes in my time (some of which I’ve written about here) and, even if it’s taken a while, I’ve learned from them. Or most of them, I reckon. Indeed, when I look back on my early years as a teacher and, to be honest, even the those that have passed much more recently, I’m struck by all the things I didn’t know and was blissfully unaware of as I clocked-in each day.

Goodall finishes the paper with a question about competence. She asks whether a leader should ‘be someone with a deep knowledge of the industry or sector or, instead, a talented manager with generic skills but little or no detailed expertise?’ I suspect anyone working in a school right now will know that answer to that one.

Thanks for reading –

Doug

.jpg?width=50&name=douglas-wise%20(2).jpg)